Explaining America’s Child Care Problem

Americans are constantly hearing about the country’s child care crisis. The topic has been featured in papers from the New York Times to Bloomberg, the subject of countless white papers (including by us), and the focus on panels and hearings in Congress.

But ask anyone to define the crisis and it’s likely you’ll get a different answer every time.

That’s because there is no one problem with child care in America. The issues are numerous and complex. Parents struggle to afford climbing child care costs. There are fewer options outside of formal day care centers. And providers are barely making ends meet.1

If we’re going to make child care easier on parents, it’s essential to drill down and define where the problems lie. In the following explainer, we break down three of the most urgent problems plaguing the child care system—affordability, access, and workforce—to help policymakers begin to identify solutions. Specifically, we explore the challenges around:

- Affordability: Parents spend a large and growing portion of their salary on child care. Providers face red tape and rising costs. And federal funds are barely making a dent in the problem.

- Access and Choice: Parents have fewer options outside formal centers. There is a dearth of options for those working non-standard hours. And parents in rural areas face long waiting lists and drive times.

- Child Care Workers: Workers get low pay and limited benefits. They also face complex credential requirements. And an anti-immigration agenda is making issues worse.

Affordability

Child care is becoming increasingly unaffordable—for both parents and the child care providers. Providers’ earnings rely on some combination of how much a family can pay and what the government can subsidize. The combined figure is usually much less than the actual cost of providing quality care, and most families are not in a financial position to easily make up the difference.2

Parents Spend a Large and Growing Portion of Their Salary on Child Care

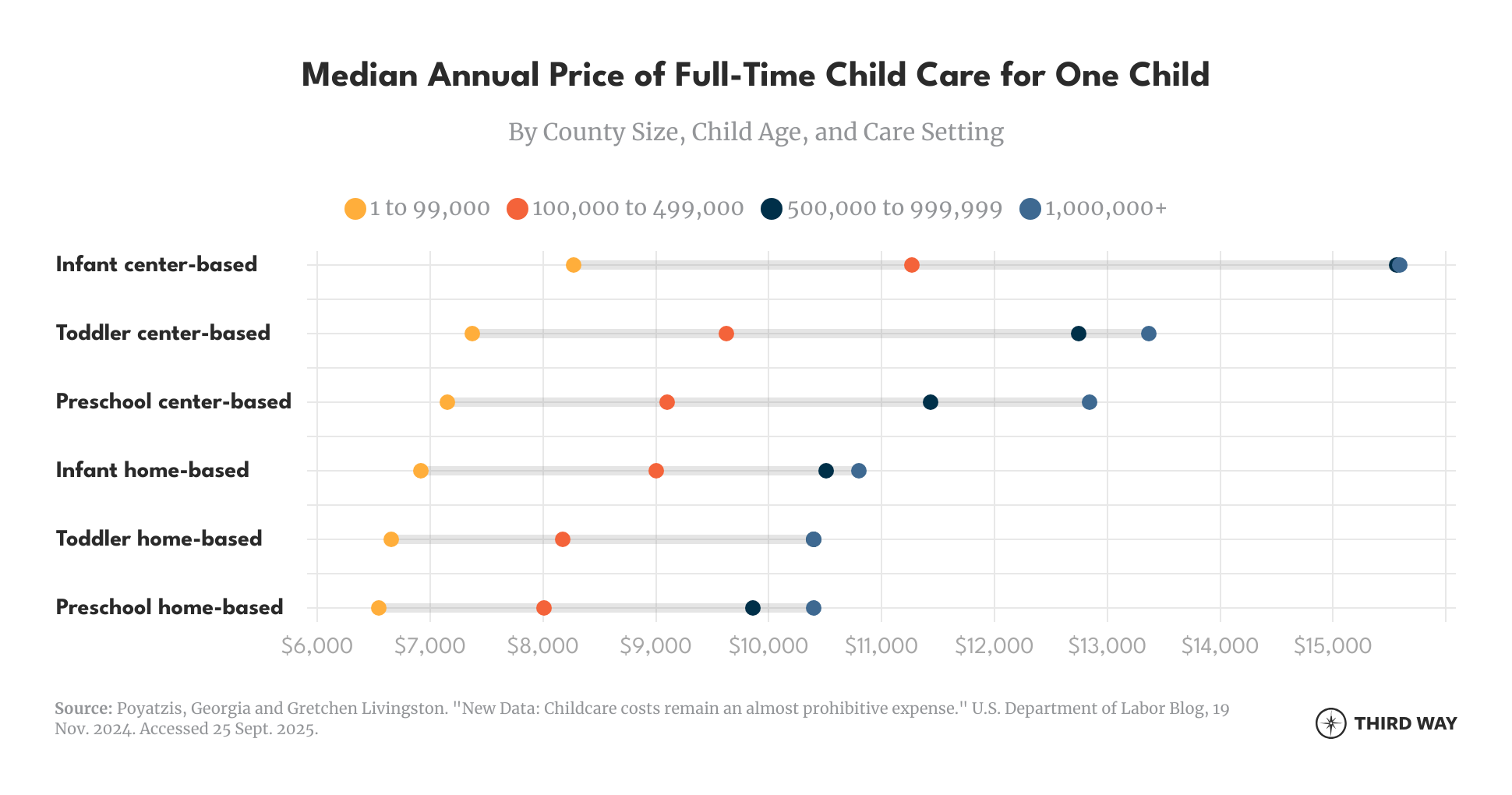

Child care costs can vary greatly for families based on the age of the child, where they live, and the type of care they are paying for. On average, parents spend between $6,500 to $15,600 per child for one year of child care.3

Child care costs continue to eat up more and more of families’ budgets. Our recent analysis found that, in inflation-adjusted terms, the average cost of child care has climbed 41% in the past 25 years.4 The median cost for full-time, center-based infant care totaled $1,200 a month in 2023—roughly 15% of the median family’s monthly income.5 Families with lower incomes are likely putting an even bigger share of their earnings toward child care.6

When quality care becomes unaffordable, parents have to find other options. This includes cutting back on work hours, relying on friends or family for child care, turning to gig work, or quitting their jobs altogether.7

Most parents of young children are expected to absorb these costs at a time in their working lives when they are least able to afford it. Research finds that the median family accrues more than three times as much wealth when their child turns 16 than in the early years of their child’s life.8 Exorbitant child care costs can prevent families from saving and building wealth at a critical time in their lives.

Providers Face Red Tape and Rising Costs

Child care providers typically operate on the slimmest of profit margins.9 As a heavily-regulated industry, child care providers must meet a wide variety of requirements, such as staff-to-child ratios, fire safety codes, and CPR requirements. And the facilities themselves must comply with state, local, and federal standards.10 This leaves little money for providers to increase staff wages, leading to high workforce turnover and shortages.

Regulatory burdens are not the only financial headwind that child care centers face. Inflation has sent the cost of essentials like rent and food climbing.11 Additionally, the cost of liability insurance is pushing up operating costs. A recent survey found that affordable liability insurance coverage was more difficult to find this year for two-thirds of child care providers.12 At the same time, parental care needs have shifted, in part because of increased telework options, and also because many parents continue to require care outside traditional nine-to-five13 Plus some families now seek to use providers intermittently as a way to minimize costs.14 These changes make it harder for providers to earn a stable income and plan accordingly.15

Federal Funds Are Barely Making a Dent

The primary source of public funding for child care is the federal Child Care and Development Fund (CCDF), a combination of mandatory and discretionary funds to support child care.16 The most well-known of these funding streams is the Child Care and Development Block Grant (CCDBG) program, which aims to help lower-income families access child care by subsidizing the cost.17 States have a lot of flexibility in how they utilize the funds. While some create slots at providers for eligible children, the majority of funding is used to subsidize the demand-side of the market by giving vouchers directly to families.18 This means, comparatively, fewer federal dollars are going toward improving the quality or supply of care.19 And although federal appropriations for CCDBG have increased in recent years, demand still vastly outweighs supply, with estimates suggesting that just 13% of eligible families receive support.20

Even when families or providers do receive federal funding, it is often not enough. Although reimbursement rates vary by state, on average federal subsidies only cover 75% of the cost of licensed care for an infant in a child care center and just 66% of the cost for an infant in a home-based care center.21 Providers are therefore disincentivized from offering child care slots to subsidy-eligible families, further tightening the supply for low-to-middle income families.

Access and Choice

Affording child care is one hurdle for families—accessing it is another. The child care sector has long faced a mismatch between supply and demand, with the need for affordable child care options greatly outpacing what is available. The pandemic then forced many child care centers to close or limit capacity, further constricting the supply.22 In the years since, there has been some bounce back in child care openings, but significant barriers to accessibility remain.

Parents Have Fewer Options Outside Formal Centers

It’s important to realize that child care options vary a lot. Center-based care is provided at a dedicated facility like a daycare center. Home-based (also called family-based), which is officially licensed or certified, is typically offered in a provider’s home and involves smaller groups of children cared for by one or two caregivers.23 Family, friends, and neighbors (FFN) are also another place people go for child care needs. Many states recognize the importance of FFN care, with this group receiving around 6% of CCDBG funding.24

While much of the conversation around limited child care access is focused on center-based care, far less is said about the need for more home-based care options. Home-based care services millions of children and is a top choice for many families. It’s also utilized more often by lower-income families, communities of color, immigrant families, and those in rural areas.25

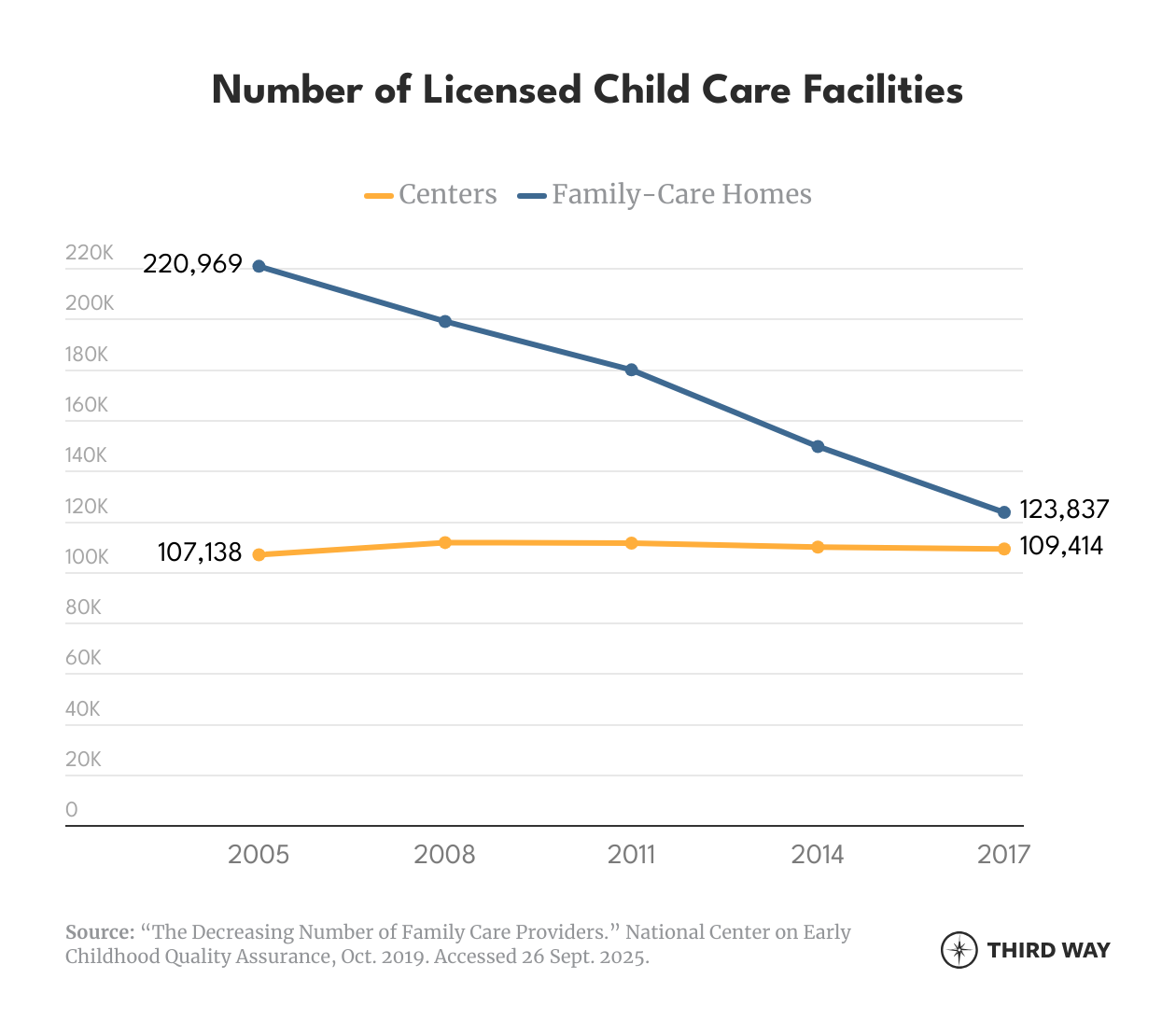

Nearly half of listed home-based child care facilities closed between 2005 and 2017. This was in part due to unpredictable income, rising rents, and an increase in regulations on providers.26 Home-based care centers also find themselves outside of child care subsidy systems as approval processes, payment logistics, and state-level policies can often make it harder for these providers to access federal funds.27 While more recent data is harder to come by, new numbers from Child Care Aware found that, in 2024, the number of licensed family care programs (both large and small) dropped down to around 98,000. The number of centers also declined to 93,000.28

This decline may be pushing families to rely on informal methods of care like neighbors or relatives, which already represents a huge part of the larger home-based care structure. A national survey from 2019 found that while there were a million paid providers caring for children in a home-based setting, just 10% were classified as licensed, regulated, or registered.29 Data surrounding why families use informal care and its impact on working families is a lot harder to track down, but some evidence suggests that informal care options are less reliable for parents and may force them to take unexpected time off work.30 Other research finds children learn meaningfully less in reading and math when in informal care compared to those in formal center settings.

There is a Dearth of Options for Those Working Non-standard Hours

In a previous report, we found that 23 million non-college workers start work in the dark, beginning their shift between 7:00 pm and 7:00 am.31

For parents working outside the traditional nine-to-five schedule, finding child care can be a nightmare. While an estimated 43% of children in the United States have at least one parent that works non-traditional schedules, just 8% of centers and a third of home-based programs are open outside normal working hours.32 State child care regulations often don’t provide guidance on what quality care looks like early in the morning or late in the evening. In addition, it can be difficult for providers to find staff to work these time slots.33

Parents in Rural Areas Face Long Waiting Lists and Drive Times

In a recent survey, 40% of families seeking a daycare slot found themselves on a waiting list with an average wait time of six months.34 For too many families, getting care when they need it is a struggle, and this is especially true for rural families where demand for care significantly exceeds supply.35 Parents in rural places face longer drive times to find child care, which often places pressure on families to have one parent leave the workforce. A survey from the Bipartisan Policy Center found that roughly four-in-ten rural parents had to leave the workforce altogether due to child care reasons.36

Child Care Workers

Increasing the supply of child care options can’t happen without a robust number of child care workers. While this workforce has rebounded to its pre-pandemic levels, there continue to be significant challenges in finding and retaining workers. In particular, the high barriers to economic stability and opportunity faced by child care workers leads to high turnover rates.37

Workers Get Low Pay and Limited Benefits

There is a clear mismatch between the level of skill and training required to be a child care worker and the compensation they receive. Child care workers often possess specialized knowledge and skills critical to providing safe and quality care. Around half of all early childhood educators based in centers have a credential specific to their field, and more than 80% have some training or education beyond high school.38 Over 60% of home-based providers have more than 10 years of experience and a third have achieved an early-childhood related degree.39

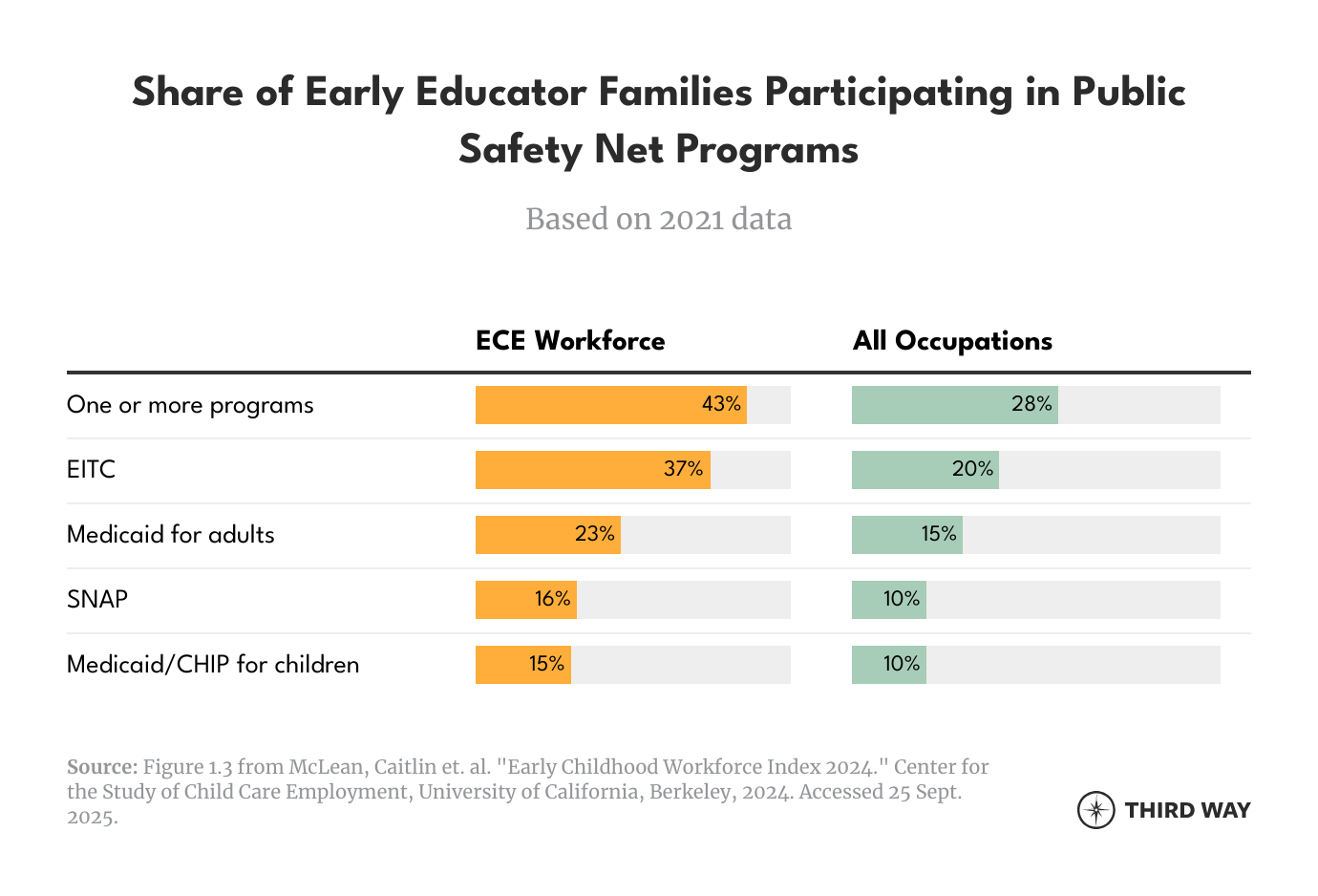

Despite playing an integral role in the education and development of young children, child care workers remain some of the lowest paid workers in our economy, with a median hourly wage of just $14.60 an hour, or $30,370 a year. For comparison, fast food workers earn $14.20 an hour—just $0.40 less.40 On top of low pay, child care workers have more limited access to key benefits. Just one-in-ten child care workers have access to retirement benefits, less than half access to employer-sponsored health insurance, and a mere quarter have access to paid sick leave.41 A lack of benefits is one of the biggest factors driving workers from the field.42

Altogether, this means that the child care workforce is more likely to live in poverty and rely on public benefits than other workers. Recent data found that over four-in-ten early educator families depend on at least one public support program—like Medicaid or food stamps.43

Workers Face Complex Credential Requirements

The licensing requirements for child care workers vary widely from state to state. To work at a child care center in Illinois, for example, you have to have a high school diploma, 60 semester hours from an accredited college, one year of experience with young children, and have completed an approved credentialing program. In nine other states, there are no requirements at all.44

Child care workers should understand health and safety protocols and be well-trained in child development and care. But burdensome licensing requirements erect unnecessary barriers that deter qualified workers from entering a field that desperately needs them.45

An Anti-immigration Agenda Is Making Issues Worse

Around 20% of child care providers and early educators are immigrants.46 Immigrant child care workers also tend to be highly educated and skilled. Pushing these individuals from the workforce will only serve to lower the quality of care being provided.47 Yet the Trump-Vance administration’s anti-immigration rhetoric and policy agenda is making it harder both to increase the number of child care workers and to protect the existing workforce. Attacks on immigrant families and the fear they create will further destabilize an already fragile industry.

Where this Leaves Families

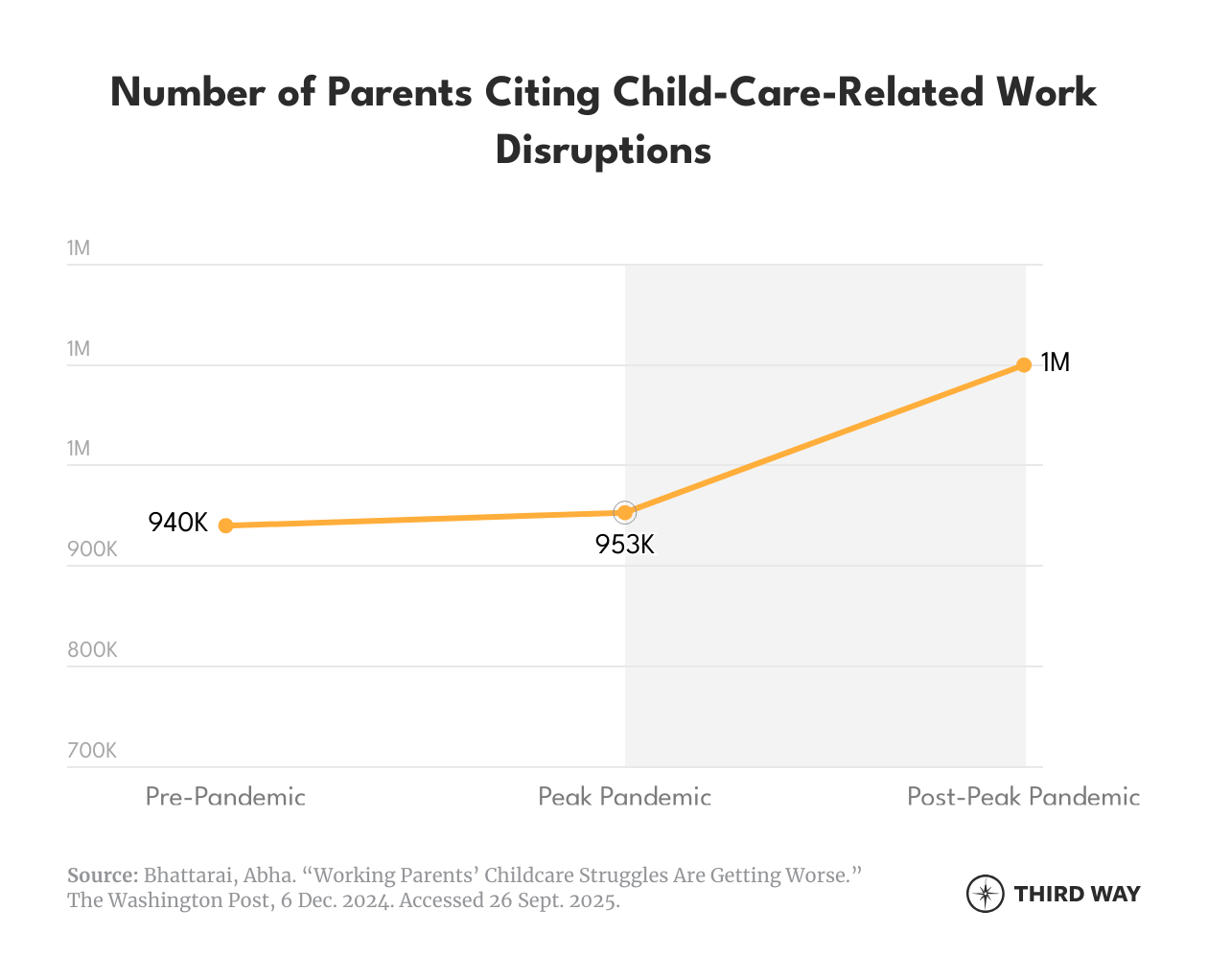

Child care costs continue to climb, and pandemic-era child care aid is long gone. As an increasing number of companies institute return to office policies, more and more parents—especially women—are taking time off work, dropping to part-time hours, or leaving the workforce altogether due to child care issues.48 More parents are now citing child care problems as why they are either quitting, taking off, or moving to part-time hours now than they did during the peak of the pandemic.49

While many states have tried to make up for the absence of more federal support, their efforts can only help so much. Take New Mexico for instance, where policymakers have decided to build a child care investment fund from the state’s surplus oil and gas revenues. But such an approach is not easily replicable in states with tighter fiscal environments.50 While in Maine, a more recent salary supplement initiative meant to support child care educators is already on the funding chopping block.51 Long-term federal support is still very much needed to address the issues outlined above.

Conclusion

America’s child care system is facing a plethora of problems. Providers struggle to provide high-quality care at affordable rates, families are getting swallowed up by rising costs, and existing federal funding is barely scratching the surface of demand.

To make meaningful progress on the issues laid out above, policymakers need to first understand where the problems exist and what is causing them. Building more child care centers that are only open from nine-to-five will help increase access for some parents—but not all. And funneling more funding into existing programs may help subsidize some costs, but it likely won’t mean an influx of home-based care centers. Tackling America’s child care problem will require a clear understanding of what parents, providers, workers, and children need, and creating a holistic vision for what a thriving child care system looks like.

Moving forward, policymakers should look towards policy levers that can address these pain points in the system with a focus on meeting families and communities where they are at.

Document ID: explaining-americas-child-care-problem